Minimum query is 3 letters.

RUBEN ÖSTLUND'S INTRIGUING OBSERVATION OF IDENTITY, MANIPULATION & COLLUSION IN 'PLAY'

By Wendy Okoi-Obuli for Shadow and Act

I watched Swedish director Ruben Östlund's film, "Play," twice. My first viewing was a really surreal moment, not just for the fascinating absurdness of the story but because the film was in Swedish with French subtitles. While I can read and understand written French better than I speak or understand spoken French (I have zero understanding of Swedish, written or spoken), there were several nuances that I missed completely first time around.

However, the film is visually appealing enough - not so much for it's stark beauty but its intrigue – that I sat through it and was able to get the general gist and feeling of quizzical WTFness and still want to see it again with the aid of some English subtitles. Thankfully, that opportunity arose with some extra screenings - this time with English subtitles.

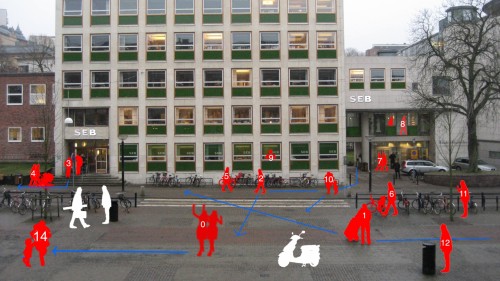

Based on a spate of real cases of bullying and robbery that took place in Gothenburg, Sweden between 2006 and 2008, "Play" is an intriguing observation of identity, manipulation and collusion. Ordinarily, a film about five black boys robbing three white boys could very easily have made a regular stereotypical story where race plays the central role. In truth, race does play a significant role here, but it's how it's used, and by whom, that's interesting.

There's the obvious divide of haves and have-nots, although there's actually nothing to suggest that the black boys come from particularly needy families. Deprivation is alluded to by the black boys themselves – in one instance to get a young white man with dreadlocks to give up his headphones, and in another instance as an excuse as to why one of the black boys engages in the crimes her perpetuates with his friends. And the notion of black boys being intimidating by their mere presence is also used, again by the black boys themselves, to get what they want. These are boys who are well aware of the stereotypes attributed to them, and they use these to engender fear, guilt and acquiescence in their victims... and all without the use of physical violence.

The ruse starts with an accusation. The time is asked by a black boy and a white boy pulls out his phone to give an answer. Already there's the slight unease on the part of the white boy, but an innocuous enough request ends up turning into questions about when and how the phone was acquired and its similarity to the phone that was stolen from the black boy's "little brother" not so long ago. This racial role reversal begins a real-time two hour journey into mind games and manipulation for sport as well as profit. The black boy leaves the small group of white boys, telling them to wait while he contacts his little brother. A game of good kid/bad kid ensues as another black boy assures the white boys of their safety by saying that he doesn't believe it's the stolen phone, even apologising for the accuser, but being certain that it can all be easily be sorted out once the little brother verifies the phone isn't his. All that needs to be done of for them to go to where little brother is, just around the corner... which ends up being two hours away on the other side of town.

The interesting thing about the film is the lack of manipulative camera angles. We're generally used to, when watching films, being shown things from a certain perspective where we either see things from the point of view of a character or are allowed to see things from our own perspective, or camera POV, before a character does, at the same time as them, or afterwards. In "Play," however, static shots, with people coming into and going out of frame, provide the kind of detachment that means the audience isn't given any particular point of view, but is forced to pay attention to everything that happens in the framed shot - drawing you in without giving you too much of a a clue or understanding as to what you're witnessing. You may have your own pre-concieved notions about why the black boys are doing what they're doing, but you also wonder why the white boys don't just leave when they get the opportunity, or just not give in to the requests (because they're not really demands) of the black boys.

Before long, you're merely a non-partisan observer of the events that unfold, not so much questioning the right or wrong of the situation, but why it's happening at all. In fact, by the end of the film, when violence is used – by an older couple of white boys who seek revenge for a theft from their own little brother, and by a white adult against one of the black boys who he knows has stolen from his son and others – you actually feel uncomfortable, not just about the violence but about the interruption of, and opposition to, the elaborate ruse.

Going back to the issue of race, the mention of skin colour is actually only mentioned, again, by the black boys themselves – late in the film to point out to the white boys how stupid they were to show their phone to a group of black boys. A woman near the end of the film who takes issue with the violent white father doesn't refer to his victim as a black boy, but as an immigrant boy, suggesting, perhaps, a certain sensitivity to race issues and/or an acute sense of civil liberties and justice. I've never been to Sweden, but the only other people of colour in "Play" are a group of South Americans who perform in native American costume to a very white audience. We later see them eating McDonalds, just like everyone else, presumably on break from "going native" for their living.

Actually, it's not entirely true that the South Americans are the only non-white people in the film. Interestingly, among the trio of white boys, one of them, John, is actually not white at all, but Chinese. His friends are at ease with him, he obviously seems to come from the same class and privileged background as them, and he's just as afraid of the black boys as they are – and perhaps even more so given a scene where he appears to be literally scared shitless. On at least two separate occasions, however, John is chosen by his white friends as buffer between them and the group of black boys – once to reason with them, and another time he's left outside a coffee shop/restaurant while his two white friends go in to seek adult assistance. Just like they all do with the black boys, John doesn't feel comfortable with this but ends up doing it nonetheless.

The most interesting thing about this film for me was not so much just the racial interplay, but observing the way in which groups of people will actually agree to take on roles which don't necessarily best serve them, whether it be to protect themselves from the threat of imminent loss or physical harm, to be liked and accepted, or to gain and maintain control of others. That it was a group of black boys doing the controlling was a fascinating scenario to watch but, even more so, was the silent shame and senseless guilt of the smaller group of non-black boys when faced with a fine for a crime they were only guilty of because of a situation they had been placed into by others who had gained power over them.

I'm not generally one to condone crime but, when one considers that the way these boys operated is a microcosm of how the world actually works on local, national, and global socioeconomic and geopolitical levels, then you can't help but wonder if they will ever readily relinquish their grasp of the understanding and use of power, and what they might do on a grander stage. A fascinating, intriguing film with plenty of food for thought.

this review by Wendy Okoi-Obuli was published on Shadow and Act, On Cinema Of The African Diaspora on January 20, 2015

FORCE MAJEURE (Turist, 2014)

An avalanche in the French Alps sends a father scurrying for his life, leaving behind his panicked wife and children, in Östlund’s examination of the conflict between social role and survival instinct.

FORCE MAJEURE (Turist, 2014)

An avalanche in the French Alps sends a father scurrying for his life, leaving behind his panicked wife and children, in Östlund’s examination of the conflict between social role and survival instinct.

PLAY (2011)

Unabashedly impolite, Östlund’s record of racially charged harassment and societal paralysis offers food for thought and fuel for fury.

PLAY (2011)

Unabashedly impolite, Östlund’s record of racially charged harassment and societal paralysis offers food for thought and fuel for fury.

INCIDENT BY A BANK (Händelse vid bank, 2009)

Based on an actual account of a bank robbery witnessed by two bystanders across the street, Östlund’s concise study of surveillance may remind some viewers of Michael Haneke’s Caché.

INCIDENT BY A BANK (Händelse vid bank, 2009)

Based on an actual account of a bank robbery witnessed by two bystanders across the street, Östlund’s concise study of surveillance may remind some viewers of Michael Haneke’s Caché.

INVOLUNTARY (De ofrivilliga, 2008)

Described by Östlund as “a tragic comedy or a comic tragedy,” the director’s second feature draws uneasy laughter through five examinations of bourgeois group dynamics.

INVOLUNTARY (De ofrivilliga, 2008)

Described by Östlund as “a tragic comedy or a comic tragedy,” the director’s second feature draws uneasy laughter through five examinations of bourgeois group dynamics.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SCENE NUMBER 6882 (Scen nr: 6882 ur mitt liv, 2005)

A young man has second thoughts about his boast to jump from a bridge in this penetrating critique of peer pressure and the fragile male psyche.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SCENE NUMBER 6882 (Scen nr: 6882 ur mitt liv, 2005)

A young man has second thoughts about his boast to jump from a bridge in this penetrating critique of peer pressure and the fragile male psyche.

GITARRMONGOT (2004)

Östlund’s mostly nonprofessional cast brings a documentary quality to this compassionate, humorous portrait of outsiders and nonconformists, focusing in particular on the titular musician, a young man facing dire obstacles in life.

GITARRMONGOT (2004)

Östlund’s mostly nonprofessional cast brings a documentary quality to this compassionate, humorous portrait of outsiders and nonconformists, focusing in particular on the titular musician, a young man facing dire obstacles in life.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.